This post originally appeared in the Simplifying Processes blog by Matt Spears.

Many of the clients I work with are just starting their process improvement journey. For the first time in years – perhaps ever – they are working intentionally to get control of their processes, instead of letting their processes have control over them. Part of this initial effort includes identifying and documenting the processes within their team, department, and/or enterprise.

Despite their best intentions, many of these process newcomers tend to struggle when it comes to identifying the processes that need to be documented for management and improvement. More specifically, they are sometimes inclined to identify processes that are not really processes at all. In other words – the scope of the “process” is too small and does not need to be managed or improved in isolation.

My aim in the content that follows is to provide some helpful and simple guidelines that will aid process champions as they identify, map, manage, and improve processes at the appropriate level of detail.

What is a process?

Since the term “process” can be used legitimately to describe work that happens in various levels of detail, we first must establish a working definition of a “process.” As I am writing this post, there are several books within arms-length of me that offer a definition for the word “process.” As to not reinvent the wheel, let us draw from Rummler and Brache:

“A business process is a series of steps designed to produce a product or service.” [1]

As I mentioned above, there are legitimate reasons for identifying processes at various levels of granularity. For that reason, I want to make two changes to the Rummler and Brache definition to come up with our working definition for this article.

A business process is a series of activities designed to contribute to the production of a product or service.

Replacing “produce a product or service” with “contribute to the production of a product or service” allows us to identify processes that exist below the highest level of process classification – since only the highest-level processes can produce a finished product or service. Furthermore, changing “steps” to “activities” helps us establish a limit to the level of granularity that will be considered a standalone process – for our purposes, we will not consider mouse clicks or keyboard strokes, in and of themselves, to be a standalone process.

Process frameworks and reference models

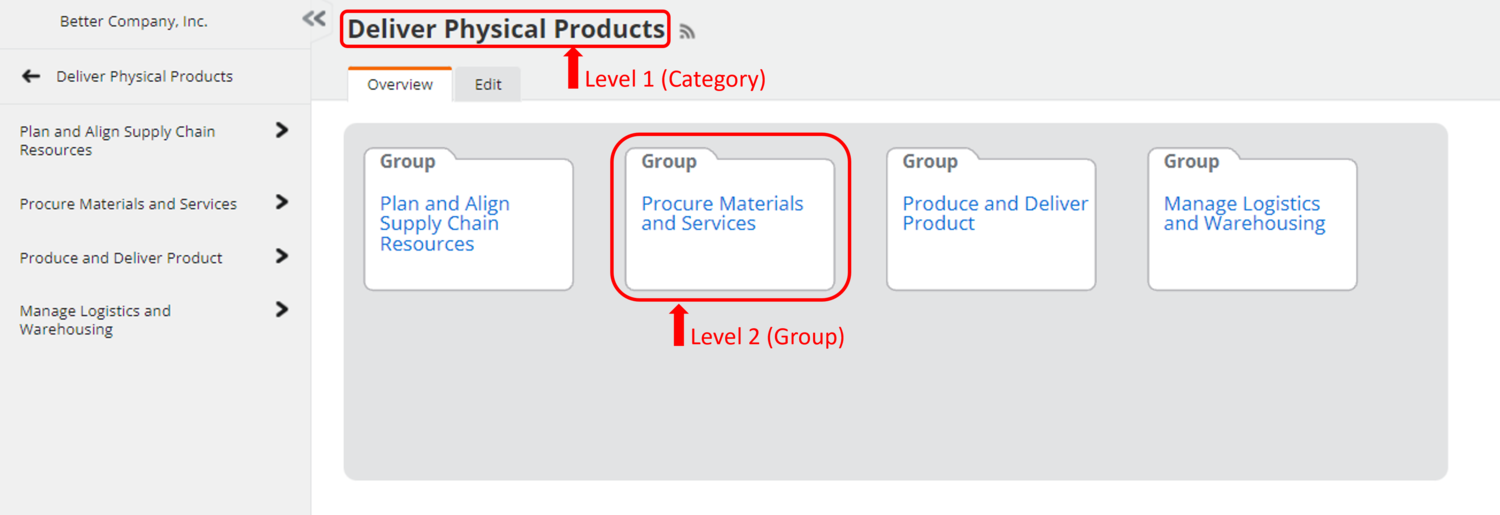

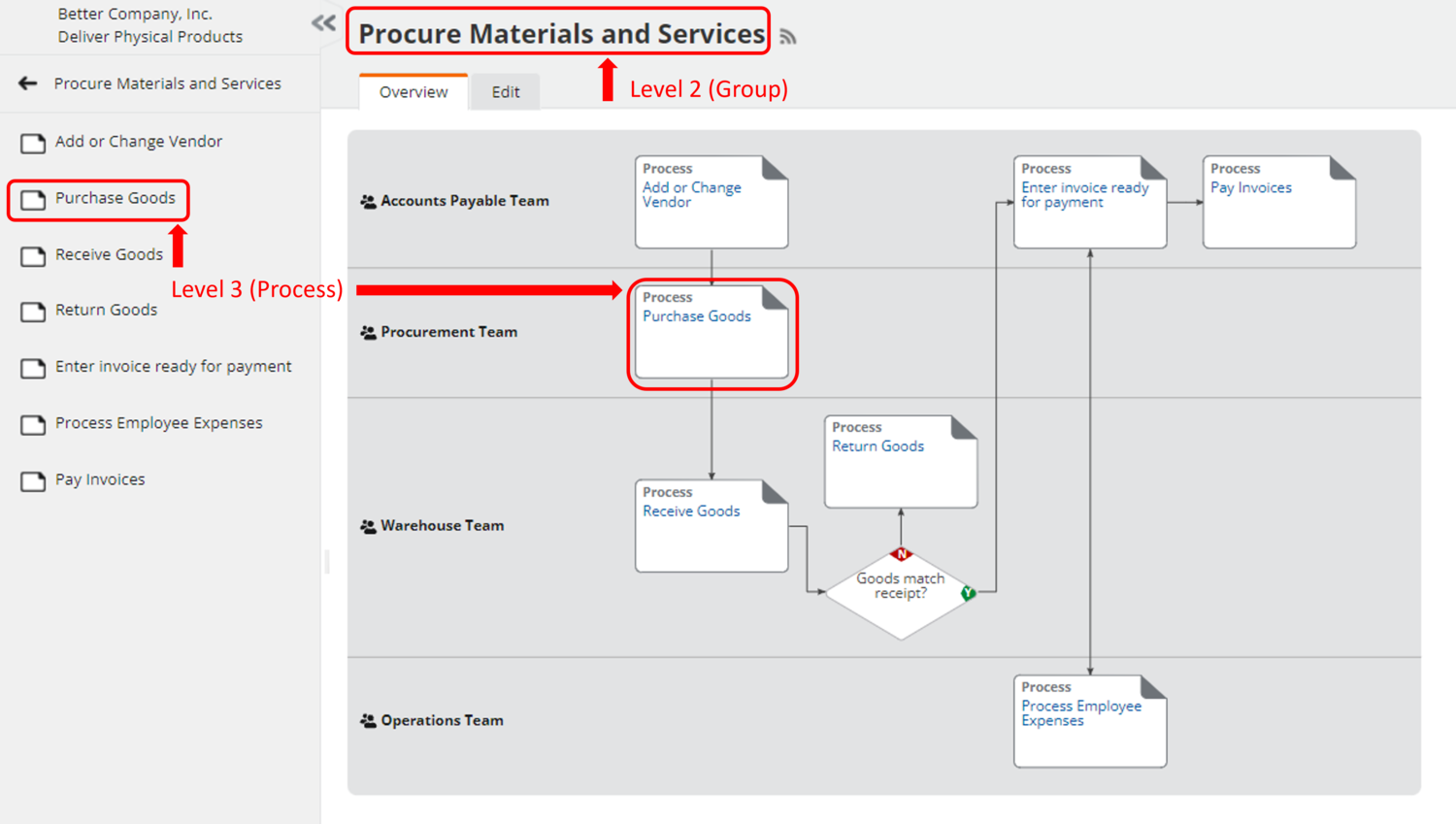

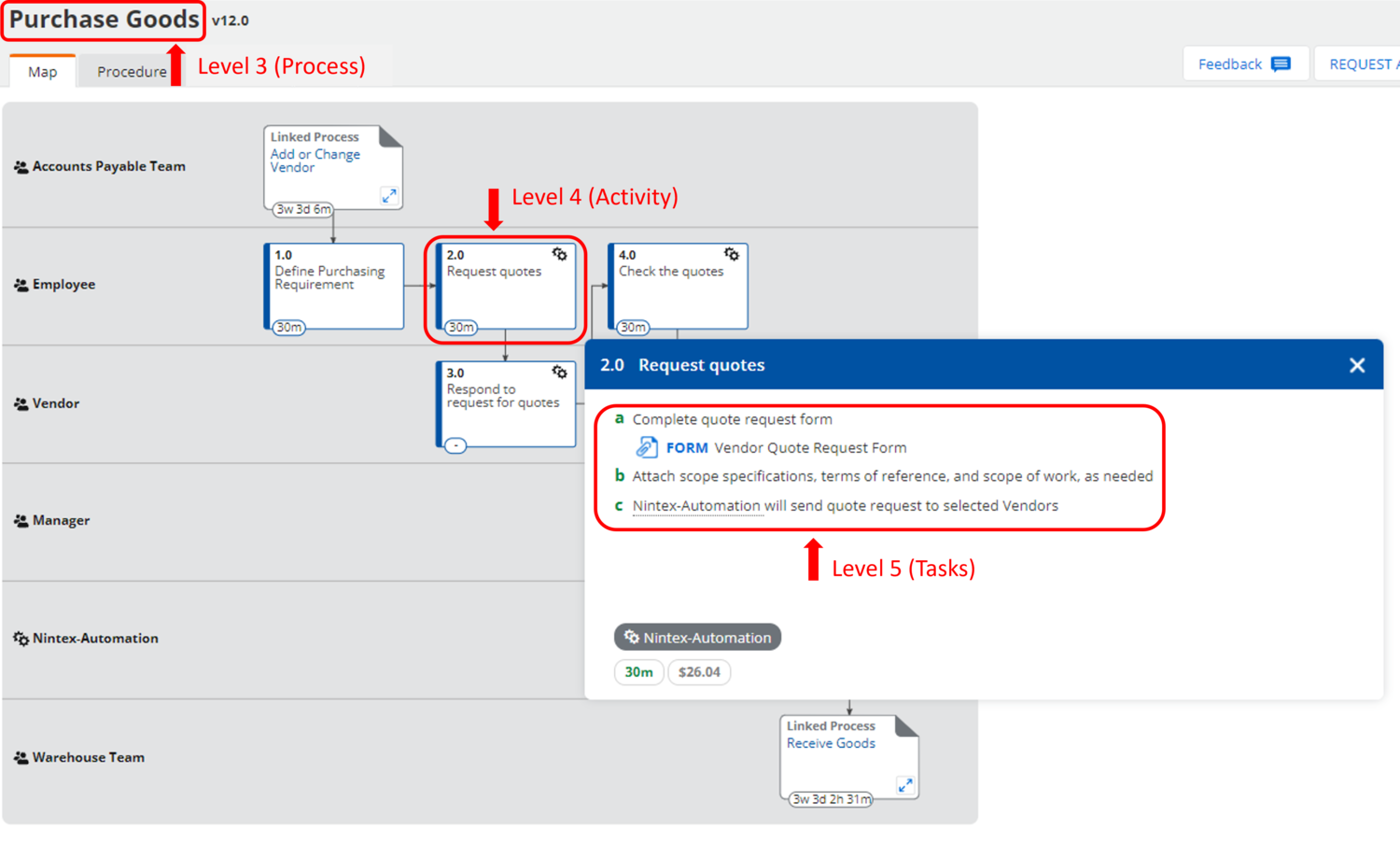

Essentially, what we have done in establishing the working definition above, is to define what many industry professionals and consortia refer to as a “Level 3 process.” In my opinion, the AQPC PCF does a fine job of breaking down processes into categories (Level 1), groups (Level 2), and processes (Level 3). The PCF also identifies activities and tasks (Levels 4 and 5, respectively). [2]

Of course, there are other frameworks that take slightly different approaches to process classification but are similarly useful. Referencing a framework to help categorize process levels can be very helpful to process champions as they seek to identify processes for mapping and improvement in their businesses. As Dumas et al. state regarding the benefits of using a process framework as a reference:

“The reuse of reference models provides several benefits. First, reference models can serve as a starting point to develop a classification of major process areas. In this way, they directly support the identification of regulatory or highly industry-specific processes…. Second, reference models may be useful to check the completeness of the processes identified by an organization.” [3]

Below is a visual example of how the five process levels identified by APQC can fit together for a Purchase Goods process built-in Nintex Promapp.

Level 1 Category and Level 2 Group

Level 2 Group and Level 3 Process

Level 3 Process, Level 4 Activity, and Level 5 Tasks

Problems with mapping processes at the wrong level

There are several problems that can occur when items that are not processes – think activities and tasks (PCF Level 4 and 5) – are mapped as Level 3 business processes. Below are a few examples.

For one, you end up with a higher quantity of processes that will each require governance and oversight resulting in potential strain on the process management (human) resources available. Why manage two or three separate processes when you can manage one? This excess number of processes will also serve to clutter the search results and burden navigation through your digital process platform, making it harder on end users to gain value from the process management effort.

Secondly, the finished product will not accurately represent the true process. If a map only captures a subset of the actual process, then that map will be incomplete. It will be missing the necessary context to give it meaning. The input and output relationships will not be properly defined resulting in a process vacuum that will limit comprehension and make improvement more difficult. The utility of the process map will also be limited from a work resource perspective.

Additionally, process metrics will be inaccurate. Mapping a snapshot of a process leads to incomplete process data. The time, cost, and quality data will only represent something that can contribute to the creation of a usable output, not the output itself. The entire Level 3 process is needed to accurately measure time, cost, or quality data.

Is it a process?

To help avoid some of the above pitfalls and to answer the all-important question (Is it a process?), it is often helpful to ask a series of questions before mapping a process:

- How many activities does the process have? If the answer to this question is three or less, you may be dealing with a subset of a process (Level 4 or Level 5 detail) and not an actual business process. If that is the case, look upstream and downstream from the process you are working on and see if it fits in better as a part of something larger.

- How many handoffs does the process have? If a process has only one actor, it is most likely not a (Level 3) business process. There, of course, can be exceptions to this. Most notably if the single actor is performing functions in multiple systems. Still, if you identify a process for mapping and it has no visible handoffs and only one actor, you might want to dig a little bit and see if it is part of something bigger.

- Does the process need to be managed by itself? A good way to answer this is to look at what the process produces – it’s outputs. Are KPIs established for those outputs? Are the KPIs monitored? What happens if they are not met? If you are having a hard time identifying any particular outputs or success measures for the process, it is probably not a standalone business process and should be mapped as part of a larger business process.

- Is this process able to be managed by one person? Different from the preceding questions, this one is designed to help you identify when you are mapping multiple processes (Level 1 categories or Level 2 groups) as a single process instead of breaking them into manageable Level 3 business processes. Processes that need to be decomposed before being mapped will typically have multiple cross-functional handoffs. If that is occurring in your process, you might want to break it into multiple smaller processes.

- Does the process fit neatly into the organizational process framework? This might be the most important of all our questions. Whether you reuse a public framework, make your own, or some combination of both – the framework should outline the organization’s core (customer facing) processes at a high-level (value stream) as well as supporting (core-enabling) and management (internal facing) processes. I mentioned the APQC PCF above – this is a very popular framework. Taking a reusable framework such as the APQC PCF, modifying it to fit the needs of your business, and incorporating organization-specific terminology makes process identification so much easier. Simply map what is missing in the identified framework! So, if the process does not have a natural fit in the organization’s framework, it might not be an actual business process.

So, is it a process?

The discipline of process management and improvement is hard enough to introduce into a business. Starting this journey by mapping processes that are not true processes will only serve to slow down progress and frustrate users. Taking time on the front-end to understand what a process is and how it fits into the organizational framework will help achieve process management results – both through improved process designs and a better-informed workforce.

[1] Geary A. Rummler and Alan P. Brache, Improving Performance (Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1995), 45.

[2] APQC.org. https://www.apqc.org/system/files/resource-file/2020-01/PPM-UnderstandingPCFElements.pdf (accessed October 12, 2021).

[3] Marlon Dumas, Marcello La Rosa, Jan Mendling, and Hajo A. Reijers, Fundamentals of Business Process Management (Springer, 2018), 46.

See how you can simplify your Process planning, mapping, and management journey here.